Can Women Get Prostate Cancer?

It’s a question that seems to defy logic: men often get prostate cancer, but can women too? The answer is yes, but with a significant caveat. Women have small glands near the urethra called Skene’s glands, sometimes referred to as the “female prostate.” These glands can develop malignant tumors, though such cases are extremely rare.

Prostate cancer in women is a vastly different issue compared to men. Literature and case reviews suggest Skene’s gland cancer occurs in about 0.003% of female genital-urinary tract cancers. This highlights just how rare these tumors are. Yet, despite their rarity, these cases are not to be underestimated. They have real consequences for women, and awareness is key for accurate diagnosis.

This article delves into the anatomy, function, and treatment of the female prostate. It explores the structure and role of the female prostate, symptoms, risk factors, and conditions that mimic cancer. It also discusses diagnostic steps, treatment options, and the challenges in researching this topic. Along the way, it poses important questions about women and prostate cancer, highlighting why understanding this topic can be critical for individual patients.

Understanding The Female Prostate: What Are The Skene’s Glands?

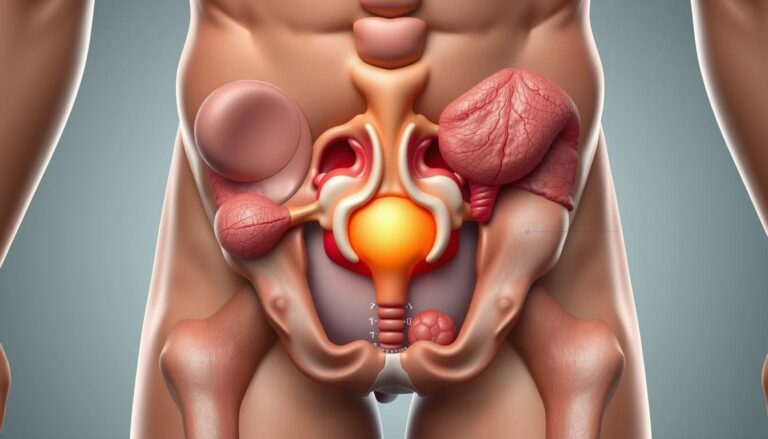

The Skene’s glands are located at the front of the vagina, near the urethra. They were named after surgeon Alexander Skene. These glands form a network of glands and ducts. The debate continues over whether they drain beside the urethra or directly into it. Their position links them to both urinary and genital anatomy.

Anatomy And Location

Microscopically, Skene’s glands resemble tiny lobules around short ducts. They are situated on the anterior vaginal wall and can be felt during a careful pelvic exam. Some researchers believe they are connected to the G-spot, though this is a topic of debate.

Due to their small size, the glands can be difficult to see without imaging. When swollen or cystic, they become more noticeable and may be mistaken for urethral issues. This overlap explains why cases once labeled as urethral problems are now reassessed as Skene’s gland conditions.

Functional Similarities To The Male Prostate

Skene’s glands produce prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and PSA phosphatase (PSAP). These enzymes are also found in male prostate health tests. PSA can appear in female tissues under certain conditions, such as some breast cancers and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Researchers believe these glands may influence urinary tract health, serve as a reservoir for microbes, or play a role in sexual response. Each function links back to broader concerns about women’s prostate health and how it fits into reproductive and urinary systems.

How Modern Imaging Has Advanced Knowledge

Improvements in MRI and transperineal sonography have sharpened views of the Skene’s glands. Radiologists can now measure gland size, spot cysts, and detect abscesses or small lesions that earlier tools missed. These advances allow clinicians to separate urethral disease from Skene’s gland pathology more reliably.

As imaging spreads, reported patterns may shift. Better detection affects estimates of female prostate cancer risk and highlights female risk factors for prostate cancer in people assigned female at birth. The result is a clearer map of how rare conditions sit within routine gynecologic and urologic care.

can women get prostate cancer

Yes, women can develop cancer from the Skene’s glands, often referred to as the female prostate. Pathologists might call such tumors Skene’s gland adenocarcinoma or female prostate cancer. This is when the cells show similarities to those found in male prostate tissue.

Direct Answer And Clinical Context

Skene’s glands produce proteins like PSA and PSAP, which can be found in some urethral and periurethral tumors. This leads clinicians to consider a glandular origin. Women experiencing unexplained urinary bleeding, a palpable mass near the urethra, or persistent urinary symptoms may undergo evaluation. This includes looking at Skene’s gland pathology as part of the differential diagnosis.

Incidence And Rarity

The reported frequency is extremely low. Older studies suggest Skene’s gland cancer accounts for about 0.003% of genital-urinary cancers in females. This means most clinicians will rarely, if ever, encounter such cases in their careers.

Due to its rarity, the evidence base is mostly based on case reports and small series. The exact numbers, typical course, and long-term outcomes are not well understood. Some researchers believe a portion of urethral or periurethral carcinomas might actually originate in Skene’s glands. This raises questions about prostate cancer gender differences and women’s risk of prostate cancer.

Signs And Symptoms Of Skene’s Gland Cancer And Related Conditions

Reports of Skene’s gland malignancy and related disorders often highlight a few key warning signs. These signs can prompt further testing and remind us that a definitive diagnosis often requires tissue sampling.

Urinary complaints and local mass effects are common indicators. Symptoms include painful urination, blood in the urine, and a palpable lump beside the urethra. Many patients also experience pressure or fullness in the pelvis and frequent urination.

Difficulty passing urine and pain during intercourse are also reported. Abnormal menstrual changes are observed alongside these symptoms. In some cases, serum PSA levels rise and then fall after treatment, similar to prostate cancer in males, raising questions about markers in female prostate cancer.

These symptoms can be misleading due to their similarity with common urogenital problems. Issues like urinary tract infections, urethritis, sexually transmitted infections, and pelvic floor dysfunction can present with similar symptoms. This confusion can delay appropriate care for women’s prostate health.

Historically, female “prostatitis” was often misdiagnosed as urethral infection. Recent research suggests that some cases may involve Skene’s gland infection instead. This shift in diagnosis impacts treatment choices and can delay necessary care.

Cysts, abscesses, benign tumors, and inflammatory swellings of the Skene’s glands can mimic cancer. Careful evaluation with targeted imaging and biopsy is often necessary to differentiate benign processes from true malignancy.

The table below summarizes common presentations, possible mimics, and the next diagnostic steps clinicians often take when symptoms of female prostate cancer are suspected.

| Presentation | Possible Noncancer Mimics | Typical Next Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Painful urination (dysuria) | Urinary tract infection, urethritis, pelvic floor spasm | Urinalysis, urine culture, pelvic exam, consider imaging |

| Urethral bleeding or hematuria | Urethral trauma, stones, cervical causes | Cystoscopy or targeted urethral imaging, lab tests |

| Palpable periurethral mass | Skene’s gland cyst or abscess, Bartholin or paraurethral benign tumor | Pelvic ultrasound or MRI, possible aspiration or biopsy |

| Pelvic pressure, frequency, retention | Overactive bladder, pelvic organ prolapse, infections | Bladder function testing, pelvic exam, imaging |

| Pain during intercourse | Vaginismus, vestibulitis, local infection | Gynecologic exam, targeted culture, consider imaging of Skene’s area |

| Elevated PSA in reports | Not classically used in women, can rise with inflammation | Repeat testing after treating infection, correlate with imaging and biopsy |

Female Prostate Cancer Risk Factors And Demographics

Research on Skene’s gland disease is limited. Most studies are small clinical series, case reports, and animal studies. This scarcity makes it challenging to provide exact figures for female prostate cancer risk. Yet, patterns begin to emerge from these studies.

Age And Hormonal Influences

Animal studies suggest age is a factor in gland changes. Gerbils show lesions and cancer-like changes increase with age. This pattern suggests age may also play a role in humans, mirroring many glandular disorders.

Hormones significantly influence the female prostate, as lab work demonstrates. Estradiol and progesterone impact tissue structure in animal models. Some gerbil data link progesterone exposure and pregnancy history with lesion formation. These findings suggest hormonal pathways that could influence women’s risk of prostate cancer.

Associated Conditions That May Alter Risk

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is noted in clinical notes as associated with larger Skene’s glands and higher PSA measurements in some women. The common factor is a higher androgen environment, which may alter gland size and function. This could influence female risk factors for prostate cancer.

Chronic infection or repeated inflammation of the Skene’s glands is another possible risk factor. Inflammation drives tissue remodeling in many organs. While human evidence is scarce, clinicians are cautious of chronic or recurrent urethral and periurethral infections.

Epidemiologic data are weak due to low case counts. This scarcity prevents robust population estimates. Most conclusions rely on small studies and extrapolation from animal work. As a result, female prostate cancer risk remains an open question in need of more systematic research.

Other Skene’s Gland Conditions That Mimic Cancer

Some pelvic complaints that raise alarm for prostate cancer in women turn out to be far more common, benign problems of the Skene’s glands. A careful clinical review separates infection, cysts, and benign growths from malignant disease. Clear diagnosis shapes treatment and avoids unnecessary radical therapy.

Infections and inflammatory syndromes can produce pain, urinary urgency, and discharge. Clinicians sometimes label persistent urethral discomfort as urethritis or urethral syndrome. Better examination can reveal Skene’s gland involvement, a pattern often called female prostatitis.

Sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhea may spread into the glands. Untreated STIs increase the chance that the Skene’s glands become infected. When the gland is the source, antibiotics alone might not be enough; targeted drainage or gland-focused therapy can be needed.

Blocked ducts lead to cysts and, at times, abscesses. These lesions most often affect people in their 30s and 40s, though they can appear at any age, even in newborns. Small, uncomplicated cysts sometimes resolve or can be drained in clinic.

Abscesses demand prompt drainage plus antibiotics. Failure to treat an abscess can cause prolonged pain and systemic infection. Proper imaging and clinical care reduce these risks and spare patients undue worry about women and prostate cancer when the cause is benign.

Benign tumors of the Skene’s glands have been reported in case studies. Examples include adenofibromas and leiomyomas. Adenofibromas may cause dyspareunia and are typically removed surgically, with good outcomes.

These noncancerous conditions are far more common than malignant ones and often present in similar ways. Awareness of Skene’s gland conditions helps clinicians consider alternatives to a cancer diagnosis and tailor less invasive care.

| Condition | Typical Age Range | Common Symptoms | Usual Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection / Female Prostatitis | Any age, often adults | Urethral pain, urgency, discharge, pelvic pain | Antibiotics, gland-targeted treatment, follow-up |

| Cysts | Newborns to 40s, most common 30s–40s | Painless lump, urinary discomfort, occasional pain | Observation, drainage if symptomatic |

| Abscess | Adults | Severe localized pain, fever, swelling | Drainage and antibiotics |

| Benign Tumors (adenofibroma, leiomyoma) | Adults | Dyspareunia, local mass, discomfort | Surgical excision, pathology confirmation |

| Malignant Disease (rare) | Usually older adults | Mass, persistent atypical symptoms | Biopsy, oncology referral, tailored therapy |

Diagnosis: How Clinicians Evaluate Suspected Skene’s Gland Cancer

When a clinician suspects a lesion near the urethra, they follow a detailed, step-by-step approach. They start by discussing urinary symptoms, pain during sex, and any visible bulge. They also consider reproductive history and past infections, which helps understand the context of possible prostate cancer in females and broader women’s prostate health concerns.

Clinical Exam And Symptom Review

They note urinary bleeding, dysuria, frequency, and dyspareunia. A pelvic and periurethral exam may reveal a palpable or visible mass on the anterior vaginal wall. Gentle digital palpation can distinguish a mobile cyst from a firm, fixed lesion that warrants further workup.

Clinicians also record sexual and obstetric history, prior pelvic infections, and STIs. Conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome or prior breast cancer can shape test interpretation and risk discussions. Symptom timing and progression guide urgency for imaging and tissue diagnosis.

Imaging And Lab Tests

MRI and transperineal sonography clarify gland enlargement, cysts, abscesses, and suspicious masses. Imaging maps the lesion’s relation to the urethra, bladder, and surrounding tissues. This anatomy is critical for planning biopsy or surgical access.

Urinalysis, urine cultures, and STI testing rule out infectious mimics before invasive steps. Some case reports note elevated serum PSA in Skene’s gland tumors and use PSA to follow treatment response. PSA can rise with PCOS or certain breast cancers, so lab results need careful clinical correlation.

Biopsy And Pathology

Tissue diagnosis by targeted biopsy or excision is essential to confirm malignancy. Pathology identifies histologic types such as adenocarcinoma or benign lesions like leiomyoma. Immunohistochemistry and specialized stains help determine origin when urethral and periurethral cancers overlap.

Accurate pathology can reclassify tumors previously thought to arise from adjacent structures, refining decisions about therapy. Given the rarity of these cases, detailed pathology reports and markers like PSA expression assist multidisciplinary teams as they weigh options for prostate cancer in females and ongoing women’s prostate health surveillance.

| Step | Purpose | Common Findings |

|---|---|---|

| History & Exam | Identify symptoms and localize lesion | Urinary bleeding, dysuria, palpable anterior vaginal mass |

| Imaging | Define size, extent, relation to urethra | MRI: solid mass or cyst; Ultrasound: periurethral enlargement |

| Laboratory Tests | Exclude infection; assess tumor markers | Urinalysis/culture negative for infection; PSA may be elevated |

| Biopsy/Pathology | Confirm histology and origin | Adenocarcinoma, adenofibroma, leiomyoma; immunostains refine diagnosis |

Treatment Options For Skene’s Gland Cancer And Related Management

Treatment for Skene’s gland issues spans from local surgeries to broader medical treatments. The choice depends on tumor size, spread, symptoms, and patient goals. Healthcare teams draw from urethral and prostate cancer treatments to find the best approach for female prostate cancer and prostate cancer in women.

Surgical Approaches

Surgery is a common treatment for Skene’s gland tumors. Small, localized tumors may be removed through local excision. Larger tumors near the urethra might need partial urethral removal with reconstruction to maintain urinary function.

Benign growths like adenofibromas, cysts, and leiomyomas are often treated with excision or drainage if they cause pain or block urine flow. Surgery can be curative if the disease is confined. Pre-surgery planning aims to preserve continence and sexual function while ensuring clear margins.

Radiation And Systemic Therapies

Radiation therapy is effective when surgery is risky or not possible. Some patients experience a decrease in PSA and symptom relief after targeted radiation.

Systemic therapy, including chemotherapy or targeted agents, depends on tumor type and spread. Due to rarity, there’s no standard regimen. Oncologists tailor systemic treatments, drawing from prostate and urethral cancer protocols.

Managing Noncancerous Skene’s Gland Conditions

Cysts and abscesses are treated with drainage and antibiotics. Recurring cysts that affect comfort or function may need removal. For infections, targeted antibiotics are the first line of treatment.

When abscesses occur, a combination of medical and surgical drainage may be necessary. Decisions consider symptom severity, lesion type, fertility and continence concerns, and patient preferences. A team approach from urology, gynecology, and oncology ensures personalized care, addressing the unique needs of female prostate cancer and prostate cancer in women.

Why Research Is Limited And What The Medical Community Is Learning

Rare diseases, like Skene’s gland tumors, are a significant challenge for science. Their rarity makes it difficult to establish clear patterns. Clinicians often rely on single reports and small case series to guide care.

Challenges Studying A Rare Condition

Old reviews estimated an extremely low frequency, near 0.003% in some series. This rarity limits statistical power and makes randomized trials impractical. Registries show confusion between urethral carcinomas and gland tumors. Misclassification blurs incidence data and clouds outcome analysis.

Ethical and logistical limits hamper large trials. Institutional teams must extrapolate from male prostate oncology and from related urothelial studies. Case-based evidence drives many clinical decisions. Pathology and registry work remain essential to clarify true rates.

Emerging Findings And Research Directions

Modern imaging such as MRI and high-resolution sonography is clarifying periurethral anatomy. Improved immunohistochemistry reveals PSA production in some glandular tissue. This progress feeds focused research on PSA biology in women.

Investigators are studying hormonal links and PSA expression in conditions like PCOS and in subsets of breast cancer. These lines of inquiry intersect with broader interest in prostate cancer gender differences and how biomarkers behave across sexes.

Calls are growing for multicenter case repositories and careful pathologic re-evaluation of archived urethral cancers to spot missed Skene’s gland origins. Coordinated data collection would strengthen Skene’s gland cancer research and help define outcomes and treatment patterns.

Prostate Cancer Gender Differences And Broader Implications For Women’s Prostate Health

The gap between common knowledge and rare reality can be wide. Male prostate cancer is among the most frequent cancers in men in the United States. In contrast, tumors from Skene’s glands are exceptionally uncommon. This contrast shapes clinical practice and public awareness.

Comparing Male Prostate Cancer And Female Skene’s Gland Cancer

Scale and epidemiology differ sharply. Men face routine screening conversations, routine PSA checks, and well-defined treatment pathways. Reports of prostate cancer in females are rare case studies, not population-level trends.

Biochemical parallels exist. Both male prostate tissue and Skene’s glands can produce PSA and PSAP. In a few documented cases, clinicians monitored PSA to follow treatment response for Skene’s gland tumors. This overlap suggests shared biology despite vastly different frequencies.

Treatment approaches can look similar when disease is local. Surgery and radiation are common choices across sexes for localized lesions. Systemic therapies for Skene’s gland malignancies lack standardization because evidence is limited. Oncologists often adapt protocols used for more common urologic cancers.

Women’s Prostate Health Awareness

Clinicians need awareness without alarm. Symptoms like urethral bleeding, a periurethral mass, or persistent urinary complaints should prompt consideration of Skene’s gland conditions alongside more common diagnoses. Early recognition lowers the chance of misdiagnosis and delayed care.

Certain health issues can change gland size or markers. Endocrine conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome may affect Skene’s glands and PSA levels. This can complicate test interpretation and symptom assessment, so context matters in evaluation.

As imaging, pathology, and reporting improve, rare Skene’s gland disorders—both benign and malignant—may appear more often in clinical records. Greater familiarity among urologists, gynecologists, and pathologists will make women’s prostate health a clearer, less mysterious topic in everyday practice.

Conclusion

The question of whether women can get prostate cancer is complex. Women do not have a prostate like men’s, but they have Skene’s glands. These glands can, in rare cases, develop cancer. The prevalence is estimated at about 0.003%, but there are documented cases of diagnosis and treatment.

Women should be vigilant about their prostate health. Symptoms like persistent urinary bleeding or pelvic pain require medical attention. Most issues are benign, but thorough evaluation is essential to rule out cancer.

Doctors use a combination of familiar tools to diagnose and treat prostate issues in women. This includes clinical exams, ultrasounds, and biopsies. While PSA testing is sometimes mentioned, its role is not well established. The focus is on tailoring treatment to each patient’s needs.

The understanding of the female prostate is evolving. Advances in imaging and pathology will likely change how we detect and treat prostate cancer in women. This makes women’s prostate health an area of ongoing interest and research.

FAQ

Can women get prostate cancer?

Yes, women can develop cancer in the Skene’s glands, often called “female prostate cancer” or Skene’s gland adenocarcinoma. These glands are similar to the male prostate and can produce prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Such cancers are rare but have been documented in case reports and small series.

What and where are the Skene’s glands?

The Skene’s glands, named after Alexander Skene, are small glands and ducts on the anterior vaginal wall near the urethra. They are located at the front of the vagina and drain into ducts beside or possibly into the urethra. They are functionally tied to the urinary and genital systems and are sometimes linked in popular accounts to the G‑spot.

Do Skene’s glands act like the male prostate?

In important ways, yes. Skene’s glands produce PSA and PSA phosphatase (PSAP), enzymes also produced by the male prostate. PSA shows up in some female tissues and may rise in conditions such as PCOS and certain breast cancers. The glands may play roles in urinary health, infection transport, and possibly sexual arousal — though some functions remain debated.

How has modern imaging changed our understanding of Skene’s gland disease?

MRI and improved sonography, including transperineal techniques, have clarified Skene’s gland size and anatomy. They help detect cysts, abscesses, and periurethral lesions that were once misattributed to the urethra. Better imaging helps distinguish urethral disease from Skene’s gland pathology and may increase recognition of both benign and malignant conditions.

How common is Skene’s gland cancer?

It is extraordinarily rare. Older reviews estimate Skene’s gland cancer at roughly 0.003% of female genital-urinary cancers. Most evidence comes from individual case reports and small series, so exact incidence and natural history remain poorly defined.

What signs and symptoms should raise concern for Skene’s gland cancer?

Presenting symptoms reported in cases include painful urination (dysuria), urethral bleeding or hematuria, a palpable periurethral mass, pelvic pressure or fullness, urinary frequency or retention, pain during intercourse, and intermittent painless urethral bleeding. PSA has been elevated in some cases and fallen after treatment.

Why can Skene’s gland problems be hard to diagnose?

Symptoms overlap with common urogenital issues — UTIs, urethritis, STIs, pelvic floor disorders, and gynecologic conditions. Cysts, abscesses, and inflammatory swellings can mimic tumors on exam and initial imaging, so careful evaluation and, when indicated, biopsy are needed to distinguish benign from malignant causes.

What risk factors or demographics are linked to Skene’s gland lesions?

Data are limited. Age appears relevant — animal work and case patterns point to older age as a factor. Hormonal influences matter in models: estradiol, progesterone, and reproductive history have been implicated in animal studies. PCOS has been associated with larger Skene’s glands and higher PSA in women, suggesting androgenic or hormonal milieu may affect risk. Chronic infection might contribute, but human evidence is sparse.

Can infections affect the Skene’s glands?

Yes. The Skene’s glands can become infected — a presentation sometimes called female prostatitis — and STIs like gonorrhea can involve the glands. Recurrent or untreated infections may lead to abscesses. Correctly identifying gland infection changes treatment choices, which may include targeted antibiotics and drainage.

What benign Skene’s gland conditions mimic cancer?

Common benign issues include Skene’s gland cysts and abscesses, which arise from duct blockage and present most often in people in their 30s and 40s but at any age. Benign tumors such as adenofibromas and leiomyomas have been reported. These conditions are more frequent than cancer and often present similar symptoms, requiring imaging or biopsy for differentiation.

How do clinicians evaluate suspected Skene’s gland cancer?

Evaluation starts with focused history and pelvic/periurethral exam, then imaging (MRI, transperineal ultrasound) to define lesions. Lab tests include urinalysis, urine cultures, and STI testing. Serum PSA has been elevated in some cases and used for monitoring. Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy or excision with histology and immunohistochemistry to determine origin and guide treatment.

What treatment options exist for Skene’s gland cancer?

Treatment is individualized. Surgery (excision or periurethral tumor resection) is common for localized disease and can be curative. Radiation has been used effectively when surgery is not feasible, with reported PSA declines after treatment. Systemic therapies (chemotherapy or targeted agents) may be considered for advanced disease, but standardized regimens are lacking due to rarity.

How are noncancerous Skene’s gland conditions managed?

Cysts and abscesses are treated with drainage and antibiotics; recurrent cysts may be excised. Infections require appropriate antimicrobials and sometimes surgical drainage. Benign tumors are typically removed surgically when symptomatic. Management balances symptom relief with preservation of urinary and sexual function.

Why is it hard to study Skene’s gland cancer and what is being done?

Extreme rarity and diagnostic overlap with urethral cancers limit large studies and randomized trials. Most knowledge comes from case reports. Improvements in imaging and immunohistochemistry, calls for tissue re-review, and proposals for multicenter registries aim to collect cases, refine diagnosis, and identify better treatment patterns.

How Does Female Skene’s Gland Cancer Compare To Male Prostate Cancer?

The tissues share biochemical parallels — both can produce PSA and PSAP — and local treatments like surgery and radiation are used in both. The scale differs sharply: male prostate cancer is common, whereas Skene’s gland cancer is almost vanishingly rare. Systemic treatment strategies for Skene’s gland malignancies are less established because of limited data.

What should clinicians and women keep in mind about women’s “prostate” health?

Awareness, not alarm. Persistent urethral bleeding, a periurethral mass, or unexplained urinary symptoms warrant medical evaluation. Infections and benign lesions remain far more likely than malignancy, but correct diagnosis — aided by imaging, PSA context, and pathology — ensures appropriate care. As imaging and pathology improve, recognition and understanding of Skene’s gland conditions may grow.