Can Women Get Kidney Stones?

Yes, kidney stones are not exclusive to men. In fact, the incidence of kidney stones in females is increasing globally and in the U.S. These stones cause sudden, severe flank pain, blood in the urine, or persistent discomfort.

Kidney stones, also known as renal calculi, nephrolithiasis, or urolithiasis, form when urine concentration is high. Small stones may pass with hydration and pain relief. Larger stones might need treatments like shock wave therapy or surgery.

This article explores the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and prevention of kidney stones in women. It aims to provide clear, conversational, and practical information for readers in the U.S. and worldwide.

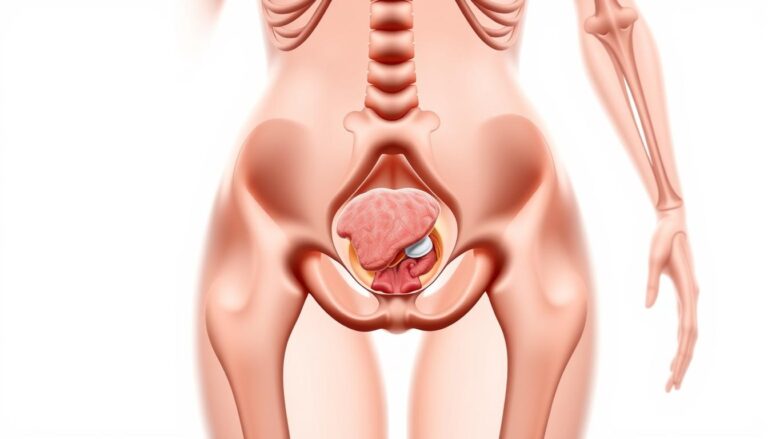

Understanding Kidney Stones And The Female Urinary System

The female urinary system is a compact, efficient network that moves waste from the blood out of the body. Kidneys filter blood and make urine. This fluid then flows down the ureters, fills the bladder, and leaves through a short urethra. Shorter urethras make urinary tract infections more common in women, but stone formation usually starts higher up in the kidneys or ureters.

What are kidney stones in plain terms? They are hard clumps of minerals and salts that form inside urine. Many stones sit quietly until movement or growth causes pain. When a stone slips into a ureter, it can block flow and trigger intense symptoms.

Kidney stones form when urine has too much of certain crystal-forming substances and not enough liquid to dilute them. Calcium, oxalate, and uric acid top the list. The balance between concentration and natural inhibitors decides whether crystals stay tiny or join into stones.

Different types of stones have different causes and implications. Calcium stones, often calcium oxalate, are the most common. Uric acid stones link to high-protein diets, dehydration, and metabolic issues like diabetes. Struvite stones grow with some infections and can enlarge fast. Cystine stones come from a rare inherited condition called cystinuria.

Can women get kidney stones? Yes, women can get kidney stones, and rates have risen among females in recent decades. Fluid intake, diet, certain medications, and medical conditions all shift risk. The female urinary system’s anatomy affects infection risk more than stone formation, but hormonal and metabolic factors play a role in how stones develop and present.

| Component | Role | Relevance To Stones |

|---|---|---|

| Kidneys | Filter blood; produce urine | Primary site where crystals form into stones |

| Ureters | Transport urine to bladder | Common location for pain when stones pass or lodge |

| Bladder | Stores urine until voiding | Stones may pass into bladder and then exit; rare source of large stones |

| Urethra | Conducts urine out of body | Shorter in women, increases UTI risk but not stone formation in kidneys |

| Urine Concentration | Reflects hydration and solute levels | High concentration increases crystal formation and stone risk |

Can Women Get Kidney Stones

Yes—women can and increasingly do get kidney stones. The experience of passing a stone often brings sudden, intense pain called renal colic. Pain may come in waves, spread from the back toward the groin, and show up with nausea, vomiting, or visible blood in urine.

Short Answer And Context

Short answer: can women get kidney stones? Plainly put, yes. Rates have climbed in recent decades and the gap between men and women has narrowed. Once a person forms a stone, the chance of a repeat event is high. Roughly half of those who have had a stone will face another episode in their lifetime.

Passage of a stone can be severe enough that patients compare it to childbirth. Emergency departments treat many cases for pain control and imaging. Stones range from tiny crystals that pass unnoticed to larger, obstructive stones that need intervention.

Epidemiology And Prevalence In Women

Historic data showed a clear male predominance. Newer trends show rising kidney stone prevalence in women, with a significant increase among middle-aged adults. Lifetime risk estimates from older studies placed men around 1 in 10 and women near 1 in 12. Recent analyses suggest that gap has tightened.

Public health patterns help explain shifting numbers. Rising obesity, higher intake of salt and sugar, and increases in type 2 diabetes among women track with climbing rates of kidney stones in females. Dietary shifts and lifestyle changes have a measurable effect on stone risk.

| Metric | Historical Estimate | Recent Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Lifetime Risk (Men) | About 1 in 10 | Relatively stable |

| Lifetime Risk (Women) | About 1 in 12 | Rising; gap narrowing |

| Recurrence After First Stone | ~50% will have another | Recurrence remains common |

| Key Drivers | Unknown factors, diet, dehydration | Obesity, high-salt/high-sugar diets, diabetes |

| Large Cohort Findings | Smaller female samples historically | Women’s Health Initiative links diet to lower risk in never-formers |

Studies such as the Women’s Health Initiative show that diets higher in fiber, fruits, and vegetables and lower in added sugars relate to lower stone risk among women who never formed stones. Despite this, women with prior stones often carry a higher recurrence risk, even with healthier eating.

Risk Factors For Kidney Stones In Women And Kidney Stone Prevalence In Women

Kidney stones in females are influenced by both daily habits and underlying health conditions. The prevalence of kidney stones in women has seen a rise in recent years. This increase is attributed to lifestyle and medical factors affecting certain groups more than others. Understanding the role of modifiable and fixed risk factors can help explain why some women are more prone to stones.

Common Modifiable Risk Factors

Drinking less water can concentrate urine, speeding up crystal formation. Women who don’t drink enough or sweat a lot in hot weather or during exercise are at higher risk. It’s recommended to aim for producing about two liters of urine daily if you’ve had stones before.

Your diet also plays a significant role. High sodium intake can increase urinary calcium excretion. Consuming a lot of animal protein and added sugars can also raise your risk. Foods high in oxalate, such as spinach, rhubarb, nuts, chocolate, tea, and beets, can contribute to calcium-oxalate stone formation if eaten excessively.

Weight and metabolism are also factors. Being overweight or having metabolic syndrome can increase stone risk due to insulin resistance and a diet rich in processed, salty foods. Taking too many calcium supplements, vitamin C, or laxatives can also contribute to stone formation.

Some medications can also increase the risk of kidney stones. For example, drugs used to treat migraines or seizures, like topiramate, can alter urine chemistry and increase stone formation. Discussing your medications with a healthcare provider can help identify and manage these risks.

Non-Modifiable And Medical Risk Factors

A family or personal history of kidney stones is a significant predictor of recurrence. Genetics and shared household habits contribute to increased susceptibility.

Medical conditions that alter urine chemistry also play a role. Conditions like gout, diabetes, hyperparathyroidism, renal tubular acidosis, cystinuria, and primary hyperoxaluria can increase stone risk. Gastrointestinal disorders and surgeries, such as gastric bypass or inflammatory bowel disease, can also affect absorption and raise the risk of stones.

Recurring urinary tract infections can lead to struvite stones. Pregnancy and hormonal changes can also affect the urinary tract, influencing both stone formation and diagnosis. Rare genetic disorders, like primary hyperoxaluria, significantly increase stone risk and may require genetic testing and specialized care.

The combination of lifestyle, medication, medical history, and genetics shapes the risk factors for kidney stones in women. This understanding helps explain the rising prevalence of kidney stones in women seen in clinics and population studies.

Symptoms Of Kidney Stones In Females And How They Can Differ

Kidney stones in females often manifest with sudden, sharp pain and a flurry of symptoms. These can vary from silent stones in the kidney to dramatic episodes when a stone moves into the ureter. The combination of urinary, abdominal, and systemic symptoms can confuse both patients and healthcare providers.

Typical Symptoms To Watch For

Pain is the primary warning sign. Women may experience sudden, severe flank or side pain below the ribs, radiating to the lower abdomen and groin. This pain, known as renal colic, can be so intense it forces someone to stop their activities.

Urinary changes are also common. Expect burning sensations while urinating, a constant urge to urinate, or passing only small amounts of urine. Blood in the urine, which can turn it pink, red, or brown, is a clear indicator to seek medical attention.

Gastrointestinal symptoms may also appear. Nausea and vomiting often accompany severe pain. Fever and chills suggest a urinary infection on top of a blocked stone, increasing the urgency for care.

Not all stones cause symptoms while they remain in the kidney. Symptoms typically begin when a stone moves into the ureter, causing obstruction or spasm. Some stones may remain silent and are discovered incidentally through imaging.

Female-Specific Symptom Considerations

Women may experience more lower abdominal or pelvic discomfort than men. This pain can mimic menstrual cramps, ovarian pain, or pelvic inflammatory disease, leading to misattribution and delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms of kidney stones in females can overlap with common gynecologic complaints. Clinicians must carefully separate pelvic causes from urinary causes through history, pelvic exam, and targeted testing.

Pregnancy adds complexity to female urinary health. Physiologic urinary changes and imaging limitations can obscure the diagnosis. Pain that overlaps with pregnancy-related discomfort requires prompt, tailored evaluation.

An obstructing stone can invite infection. Fever, rigors, or signs of sepsis indicate urgent evaluation, as infection on top of obstruction can be life-threatening.

Some women notice symptom timing that seems to follow their menstrual cycle. This pattern can complicate subjective reporting and delay recognition that kidney stones in females are the cause.

How Kidney Stones Are Diagnosed In Women

Flank pain, blood in urine, or fever can signal a serious issue. A thorough clinical evaluation is key. It involves a detailed history and a physical exam. This helps distinguish between various causes, such as urinary, gynecologic, or gastrointestinal problems.

Clinical Evaluation And When To See A Doctor

Urgent care is essential for severe pain, fever with flank pain, or trouble passing urine. Visible blood in the urine also warrants immediate attention. These symptoms often indicate an obstruction or infection that requires prompt treatment.

Doctors will inquire about past kidney stones, family history, diet, medications, and pregnancy status. The physical exam focuses on abdominal and flank tenderness. For women of childbearing age, pregnancy testing and pelvic exams are used to differentiate between gynecologic and urinary issues.

Tests And Imaging Used

Urinalysis is the first step. It checks for blood, infection, and crystals. If infection is suspected, a urine culture is performed. Blood tests evaluate kidney function, electrolytes, white blood cell count, and uric acid levels when necessary.

A non-contrast CT scan with a stone protocol is the most effective tool for diagnosing kidney stones in non-pregnant adults. It accurately shows stone size, location, and any blockage.

Renal ultrasound is preferred during pregnancy and when avoiding radiation is critical. It detects hydronephrosis and larger stones but may miss small ureteral stones. A plain abdominal X-ray (KUB) can reveal radiopaque calcium stones but misses radiolucent types.

If a stone is passed or removed, analyzing its composition guides prevention. For recurrent episodes, a metabolic workup is conducted. This includes 24-hour urine collections and targeted blood tests to identify abnormalities in calcium, oxalate, uric acid, and citrate.

These diagnostic steps lead to personalized care. They connect the diagnosis of kidney stones to ongoing female urinary health and future prevention planning.

Treatment Options For Kidney Stones In Women

Care for kidney stones in females spans from watchful waiting to surgery. Small stones may pass with time, provided pain and infection are managed. The choice of treatment depends on several factors, including stone size, location, composition, pregnancy status, and the presence of infection or obstruction.

Conservative And Medical Management

Many tiny stones can clear on their own. Doctors often recommend aggressive hydration to enhance urine flow and alleviate pain. They may also prescribe NSAIDs or, in severe cases, short courses of opioids.

Alpha-blockers, such as tamsulosin, can relax the ureter, aiding in stone passage. For suspected uric acid stones, urinary alkalinization with potassium citrate can dissolve them over weeks. Allopurinol is used to reduce uric acid production in recurrent cases.

When infection is present, immediate antibiotic treatment is necessary. An infected, obstructed kidney is a medical emergency requiring urgent decompression before definitive treatment.

Medical prevention strategies include thiazide diuretics for calcium stones and potassium citrate for mixed types. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) can also reduce oxalate production in some patients. Specialized drugs like lumasiran (Oxlumo) and nedosiran (Rivfloza) treat rare metabolic causes such as primary hyperoxaluria.

Procedural And Surgical Treatments

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) uses focused shock waves to fragment stones noninvasively. ESWL is most effective for certain sizes and locations in the kidney. It is generally avoided in pregnancy.

Ureteroscopy involves passing a scope through the urethra and bladder into the ureter to retrieve or laser-fragment stones. This method is suitable for many ureteral stones and some renal stones.

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) removes large or complex stones through a small flank incision. PCNL is the preferred option for bulky or staghorn calculi that resist other approaches.

Temporary drainage with a ureteral stent or percutaneous nephrostomy provides immediate relief for obstruction or severe infection. These measures stabilize the patient before definitive treatment.

In pregnant patients, ultrasound-guided drainage or ureteroscopy is favored to protect the fetus. CT scans and ESWL are typically avoided during pregnancy.

Choosing the right treatment balances risks and benefits. Urologists consider stone size, composition, anatomy, infection, comorbidities, prior surgeries, and patient preference to recommend tailored treatment options for kidney stones in women.

Prevention Of Kidney Stones In Women

Preventing kidney stones is often easier than treating them. Making small, daily choices can significantly impact prevention. This section will outline practical steps for preventing kidney stones and medical paths for those at higher risk.

Lifestyle And Dietary Measures

Hydration is key in preventing kidney stones. Aim for a urine output of nearly two liters a day after a stone episode. Increase fluids in hot weather or during intense physical activity. Light-colored urine is a simple indicator of proper hydration.

Reducing sodium intake can lower urinary calcium levels. Avoid processed foods, canned soups, and salty snacks. Be cautious of hidden salt in restaurant dishes, opting for fresh, homemade meals when possible.

Balance animal protein with plant-based sources. Excessive meat and sugary drinks increase stone risk. Include fiber-rich foods and moderate amounts of fish, poultry, and legumes for balanced protein intake.

Manage oxalate intake by pairing high-oxalate foods with calcium-rich ones. Foods like spinach, nuts, chocolate, beets, and tea are high in oxalate. This pairing reduces oxalate absorption.

Ensure a normal dietary calcium intake from food sources. Avoid cutting calcium without a doctor’s advice. If supplements are necessary, take them with meals and consult with a healthcare provider about dosage and timing.

Weight management is also important. Gradual, sustainable weight loss can lower the risk of kidney stones. Focus on steady habits, including regular physical activity, balanced meals, and realistic weight loss goals.

Avoid high-dose vitamin C and unnecessary calcium pills without a doctor’s guidance. Some supplements and medications can increase stone risk. Always review over-the-counter products with a healthcare provider.

Medical Prevention And Follow-Up

For those with recurrent stones, a 24-hour urine test is often ordered. This test measures various substances in urine, guiding personalized prevention plans.

Medications can target specific issues. Thiazide diuretics are used for hypercalciuria, while potassium citrate can help prevent calcium and uric acid stones. Allopurinol treats high uric acid levels. Rare conditions may require thiol drugs or newer agents.

Genetic causes have specific treatments. Therapies like lumasiran are available for certain metabolic disorders. Specialists determine if these treatments are appropriate for a patient’s condition.

Regular follow-up is essential for those prone to stones. Periodic imaging and metabolic testing track progress. Referral to a urologist or nephrologist with expertise in stones is recommended for complex or frequent cases.

Understanding individual risk factors for kidney stones in women is vital. Combining consistent lifestyle habits with tailored medical care offers the best chance at preventing kidney stones.

Female Urinary Health Considerations And Special Populations

Pregnancy and other life stages significantly alter the urinary tract, impacting female urinary health. The collecting system expands, urine composition changes, and symptoms can mimic other conditions. Clinicians must balance the safety of both the mother and the fetus when addressing flank pain or suspected obstruction.

Pregnancy And Kidney Stones

Ultrasound is the preferred initial imaging in pregnancy to minimize radiation exposure. CT scans are generally avoided unless absolutely necessary. Management focuses on pregnancy-safe pain relief and antibiotics for infection concerns. Ureteroscopy and temporary stenting are considered when obstruction causes pain or threatens kidney function. Shock wave lithotripsy is contraindicated during pregnancy due to fetal risk.

Obstruction combined with infection during pregnancy can escalate quickly. Obstetricians and urologists often collaborate to determine if conservative care is feasible or if an intervention is urgent. The goal is to preserve kidney function while minimizing fetal risk.

Recurrent Stones And Referral To Specialists

Patients experiencing repeated episodes require a thorough metabolic workup. This includes 24-hour urine collections, stone composition analysis, serum testing, and a detailed dietary review. These results guide targeted prevention strategies and medication choices.

Referral criteria include frequent recurrences, large or complex stones, single-kidney patients, impaired renal function, stones linked to metabolic or genetic disorders, and recurrent urinary infections. Urology and nephrology specialists collaborate for surgical planning or long-term metabolic control.

Genetic testing is increasingly important for monogenic causes of stones. Recent literature highlights tailored therapies for specific disorders. Dietitians with expertise in kidney-stone prevention add value by creating practical meal plans to reduce recurrence risk.

| Population | Key Concerns | Preferred Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | Diagnostic limits, fetal safety, obstruction risk | Ultrasound first, pregnancy-safe meds, ureteroscopy/stent if needed |

| Recurrent stone formers | Metabolic causes, high recurrence, possible genetic disorders | 24-hour urine, stone analysis, specialist referral, tailored prevention |

| Solitary kidney or impaired function | High stakes for loss of renal function | Early urology/nephrology involvement, aggressive surveillance |

| Patients with infections | Obstruction plus infection raises sepsis risk | Prompt antibiotic therapy, drainage when obstructed |

Conclusion

Women can develop kidney stones, and their occurrence has increased in recent years. These stones may be asymptomatic or cause severe pain. It’s critical to seek immediate medical attention if symptoms like sharp pain, blood in urine, or fever occur.

Preventing kidney stones involves simple yet effective habits. Drinking enough fluids, reducing salt intake, and maintaining a healthy weight are key. Small dietary adjustments and changes in travel habits can significantly impact prevention. For those experiencing recurring stones, a metabolic evaluation is essential to develop targeted prevention strategies.

Treatment for kidney stones varies based on the severity and type of stone. Options include conservative management, pain relief, and more invasive procedures like shock wave lithotripsy or ureteroscopy. Medical interventions may include thiazide diuretics, potassium citrate, or allopurinol. A team of specialists, including urologists, nephrologists, and dietitians, can create a personalized treatment plan. This may include targeted therapies for genetic conditions.

Preventing kidney stones is an ongoing journey. By making conscious choices about diet, hydration, and lifestyle, women can reduce their risk. With the right combination of lifestyle adjustments and medical care, most women can avoid recurring pain and maintain their mobility.

FAQ

Can women get kidney stones?

Yes, women can and do get kidney stones. These are hard mineral deposits in the urinary tract. They form when urine concentration allows crystals to aggregate. The size, type, and location of the stone determine if it passes naturally or needs medical intervention.

How common are kidney stones in women compared with men?

Historically, men had higher rates, but the gap is narrowing. Women, and middle-aged women in particular, are seeing more cases. This rise is linked to obesity, diabetes, and dietary changes. Lifetime risk estimates are now closer to parity between genders in many populations.

What part of a woman’s urinary system is affected by stones?

Stones form in the kidneys and can move down the ureters to the bladder and urethra. The female urinary system includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and a shorter urethra than men. Urethral length does not affect where stones form. Concentrated urine and poor flow increase the risk of crystal formation in the upper urinary tract.

What are the main types of kidney stones and what causes them?

Common types include calcium, uric acid, struvite, and cystine stones. Calcium stones often relate to dietary oxalate, high sodium, or metabolic issues. Uric acid stones are linked to dehydration, high-protein diets, gout, and metabolic syndrome. Struvite stones form with urinary tract infections. Cystine stones are due to cystinuria, a genetic condition.

What symptoms suggest a woman has a kidney stone?

Symptoms include sudden, severe flank pain radiating to the lower abdomen and groin, intense pain waves (renal colic), blood in the urine, painful urination, urgency, nausea, and vomiting. Fever and chills may indicate infection, requiring urgent care. Many stones are painless in the kidney but become symptomatic when they move to the ureter.

Do kidney stone symptoms differ for women?

Yes, women may experience lower abdominal or pelvic discomfort mistaken for gynecologic pain, menstrual cramps, or pelvic inflammatory disease. This can delay diagnosis. Pregnancy and menstrual cycles can complicate symptom interpretation. Seek medical evaluation for severe pain or signs of infection.

When should a woman see a doctor for suspected kidney stones?

Seek immediate care for severe pain, inability to urinate, visible blood in urine, fever, or chills, or persistent nausea and vomiting. Consult a doctor if symptoms recur, you have a prior stone, a solitary kidney, or conditions like diabetes or immunosuppression.

What tests diagnose kidney stones in women?

Urinalysis checks for blood, infection, and crystals. Blood tests assess kidney function and metabolic contributors. Non-contrast CT scans are the most sensitive for adults but avoided in pregnancy. Renal ultrasound is preferred in pregnancy and for radiation avoidance. Plain abdominal X-rays can detect some stones. Passed stones should be analyzed in a lab.

How are small kidney stones treated conservatively?

Many small stones pass with time. Treatment includes hydration, pain control (often NSAIDs), and sometimes alpha-blockers to aid passage. Uric acid stones may respond to urinary alkalinization with potassium citrate. Antibiotics are needed for infection.

When are procedures or surgery needed, and what are the options?

Procedures are used for large or complex stones, persistent obstruction, severe pain, or infection. Options include ESWL, ureteroscopy with laser, and PCNL for large stones. Temporary drainage with stents or nephrostomy tubes is used for infected obstruction. Pregnancy affects choice — ESWL is generally avoided; safer options include ureteroscopy or ultrasound-guided drainage.

How can women reduce their risk of first-time or recurrent stones?

Hydration is key — aim for 2 liters of urine output daily if prone to stones. Reduce sodium and excessive animal protein, and moderate high-oxalate foods. Pair oxalate foods with dietary calcium to limit absorption. Maintain a healthy weight, avoid high-dose vitamin C and calcium supplements without advice, and manage diabetes or metabolic syndrome. A renal dietitian can provide tailored guidance.

What medical prevention is available for recurrent stones?

For recurrent stones, clinicians may order 24-hour urine testing. Medications include thiazide diuretics, potassium citrate, allopurinol, and specific agents for cystinuria or rare genetic disorders. New targeted drugs, like lumasiran for primary hyperoxaluria, are available for select conditions.

How are kidney stones managed during pregnancy?

Pregnancy complicates diagnosis and treatment. Ultrasound is the preferred imaging. Treatment prioritizes maternal and fetal safety: pain relief and antibiotics chosen for pregnancy, and ureteroscopy or stenting used when needed. ESWL is contraindicated during pregnancy. Obstruction with infection requires urgent urologic care.

When should women be referred to a specialist for kidney stones?

Refer to urology or nephrology for multiple recurrences, large or complex stones, stones in a solitary kidney, impaired renal function, recurrent infections, or suspected metabolic or genetic causes. Specialists guide metabolic workups, advanced procedures, and long-term prevention strategies.